The Barakah Nuclear Energy Plant in Abu Dhabi, UAE, serves as a blueprint for the GCC

The Barakah Nuclear Energy Plant in Abu Dhabi, UAE, serves as a blueprint for the GCC

Following Singapore’s measured approach, the Kingdom should invest in capability now, preserve options for deployment later, and ensure it controls its energy destiny

Nuclear energy represents Bahrain’s most viable pathway toward sustainable energy independence, offering a reliable, low-carbon baseload solution that addresses the Kingdom’s fundamental constraint: simultaneously meeting soaring industrial demand whilst honouring net-zero commitments within its 786 sq km land area.

The technology would enable Bahrain to maintain energy security without perpetuating carbon-intensive generation, providing round-the-clock capacity that intermittent renewables cannot deliver at the scale required by aluminium production and desalination infrastructure.

For small Gulf states confronting identical geographical and industrial pressures, nuclear power functions not merely as diversification but as strategic necessity.

It’s the only proven technology capable of supplying gigawatt-scale baseload without territorial consumption or weather dependency.

Bahrain’s emerging interest in small modular reactor (SMR) technology signals recognition that its measured approach to nuclear readiness offers a viable template for small states navigating impossible energy trilemmas.

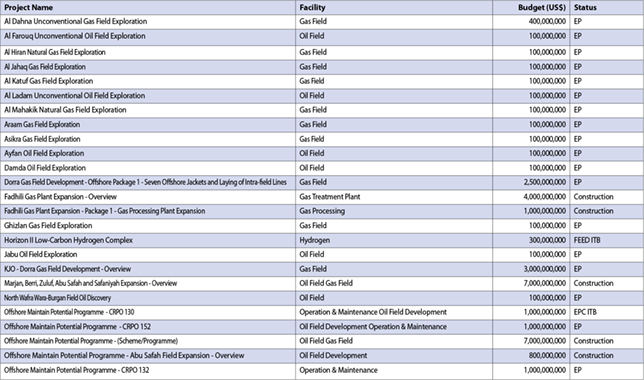

Electricity consumption has steadily risen over the last 10 years, rising from 16 GW in 2015 to 19 GW in 2024. That’s a a 15 per cent increase occurring alongside commitments to achieve 20 per cent renewable energy capacity by 2035.

With a small land area and per capita energy consumption ranking among the world’s top five, the mathematics of solar-only decarbonisation simply fail.

Current SMR designs occupy approximately 40,000 sq m per 300-megawatt (MW) unit, according to World Nuclear Association specifications.

Equivalent solar capacity would require 15-20 sq km of dedicated land, approximately 2.5 per cent of Bahrain’s total territory for a single baseload replacement unit.

A hypothetical 300-MW small modular reactor operating at 90 per cent capacity factor delivers 2,365 GW-hours annually, replacing approximately 1,200 MW of solar capacity when accounting for intermittency and storage losses.

THE SINGAPORE PARALLEL

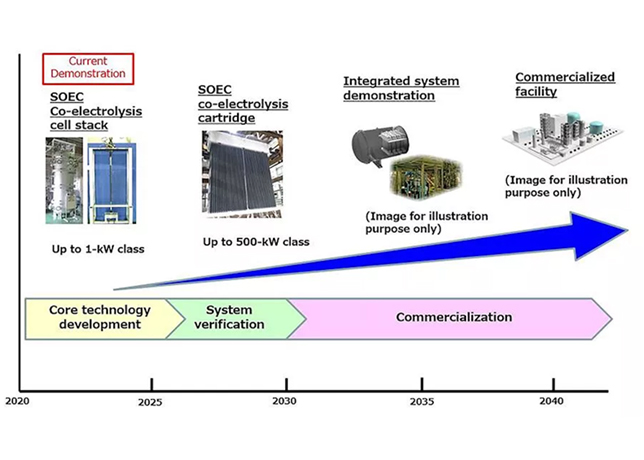

Singapore’s systematic capability-building programme provides the essential precedent for how resource-constrained states should approach nuclear energy without gambling national budgets on unproven implementation timelines.

In 2022, its Energy Market Authority report concluded that nuclear energy could supply approximately 10 per cent of national requirements by 2050, supporting net-zero targets without commitment to deployment.

The city-state is conducting comprehensive safety and feasibility assessments of advanced nuclear technologies, focusing explicitly on small modular reactors rated below 300 MWs.

Bahrain’s recent signals mirror this trajectory.

Mark Thomas, Bapco Energies Group CEO, confirmed at the Middle East Petroleum & Gas Conference that the country is exploring SMR deployment in the 2030s.

The Kingdom has signed a Country Programme Framework with the International Atomic Energy Agency for 2024-2029, establishing cooperation pathways without binding deployment commitments.

REGIONAL PRECEDENT

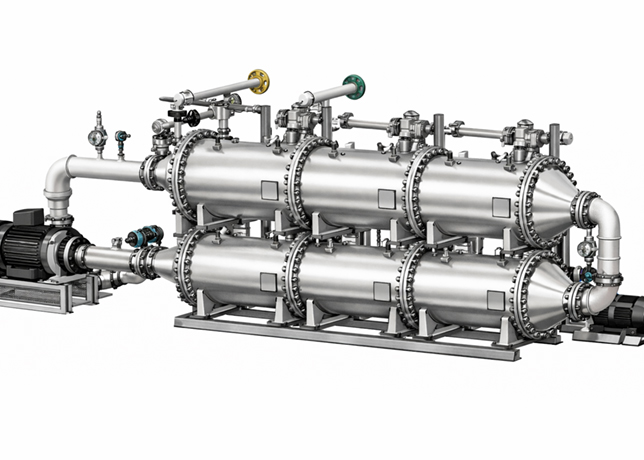

The United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) Barakah nuclear plant provides the most proximate reference case for Bahrain, both evidence of implementation challenges and proof that Arab Gulf states can execute large-scale nuclear programmes.

Barakah’s four APR-1400 reactors now supply approximately 25 per cent of UAE electricity, preventing 22 million tonnes of annual greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to removing nearly five million vehicles from roads.

The path to this achievement, however, illuminates why Bahrain should favour Singapore’s gradualist approach.

Barakah’s initial $20 billion budget escalated to $32 billion by 2020, a 60 per cent cost overrun that transformed project economics, reported by Power Technology.

This and other examples from around the world underscore why Bahrain cannot simply replicate UAE’s traditional gigawatt-scale approach but must instead pursue the SMR favours.

Beyond construction and cost challenges, nuclear deployment in the Arabian Peninsula confronts distinctive operational and security vulnerabilities.

Barakah’s Arabian Gulf cooling water source operates at 33-34 deg C, approaching thermal limits for conventional nuclear cooling systems and potentially worsening with climate change.

In December 2017, Yemen’s Houthi rebels claimed launching cruise missiles toward Barakah, highlighting vulnerability concerns in a region experiencing the world’s highest frequency of aerial attacks on nuclear facilities.

Security and safety considerations matter acutely for Bahrain given its small size and dense population distribution.

Emergency planning zones for SMR typically span 5-10 km, potentially encompassing significant residential areas in Bahrain’s compact geography where population density reaches 2,115 people per sq km.

Additionally, Bahrain must invest years building domestic expertise before any reactor commissioning.

ECONOMIC LOGIC & FINANCIAL REALISM

The industrial economics driving Bahrain’s nuclear consideration diverge sharply from residential electricity narratives.

Aluminium Bahrain (Alba) operates the world’s largest smelter outside China, producing 1.548 million metric tonnes annually with power consumption equivalent to the kingdom’s entire national grid; approximately 4,200 MWs of continuous baseload demand.

Barakah’s operational experience validates nuclear’s cost competitiveness despite construction overruns.

Robin Mills of Qamar Energy projected Barakah electricity costs at approximately 11 US cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh), remaining competitive for reliable low-carbon baseload despite delays.

Finland’s Olkiluoto 3, among the world’s most expensive nuclear projects at EUR11 billion, still delivers electricity at 7 cents per kWh over its operational lifetime, less than one-quarter the 32 cents per kWh Germany’s solar programme costs when accounting for total subsidies.

The economic case for SMRs, however, remains contested territory requiring transparent assessment.

Ontario Power Generation’s Darlington project, featuring four GE Hitachi BWRX-300 reactors totalling 1,200 MW, carries a CAD20.9 billion budget, or approximately CAD17,400 per installed kilowatt.

NuScale’s Idaho project demonstrated the volatility inherent in nascent technologies.

Target power prices escalated from $58 per MW-hour in 2021 to $89 per MW-hour by 2023, a 53 per cent increase driven by construction cost escalation from $5.3 billion to $9.3 billion for 462 MW.

These figures require contextualisation against Bahrain’s alternatives.

Solar-plus-storage configurations for baseload applications deliver levelised costs of $135-184 per MW-hour according to Ontario’s Independent Electricity System Operator comparative analysis, substantially above nuclear projections even accounting for cost overruns.

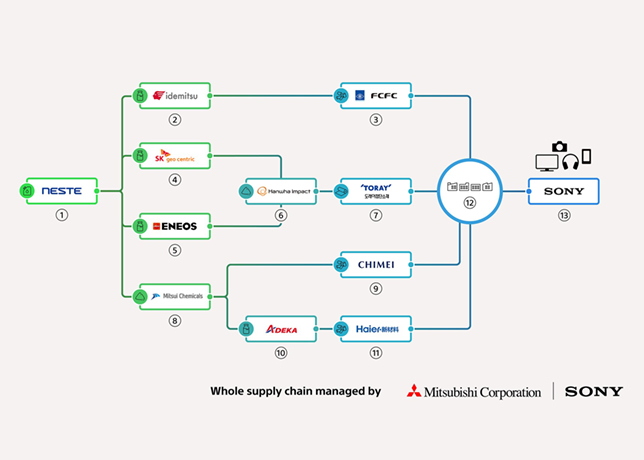

However, Bahrain’s comparative advantage lies in potential demand aggregation.

Pairing SMRs with continuous industrial load, potentially supplemented by desalination requirements and future green hydrogen production, creates anchor tenancy that reduces per-unit financing costs.

Singapore lacks equivalent industrial concentration, making Bahrain’s nuclear economics potentially more favourable despite smaller state resources.

Regional coordination through proposed GCC frameworks could further distribute capital requirements.

The Baker Institute for Public Policy’s December 2024 analysis noted that member states hosting nuclear plants could share planning costs with partners like Bahrain, Kuwait, and Qatar.

Realistic SMR reactor deployment would not eliminate Bahrain’s hydrocarbon dependence nor should that be the objective.

Two 300-MW units operating at 90 per cent capacity factor would generate approximately 4,730 gigawatt-hours annually, covering roughly 25 per cent of Bahrain’s 2024 generation of 19,009 gigawatt-hours.

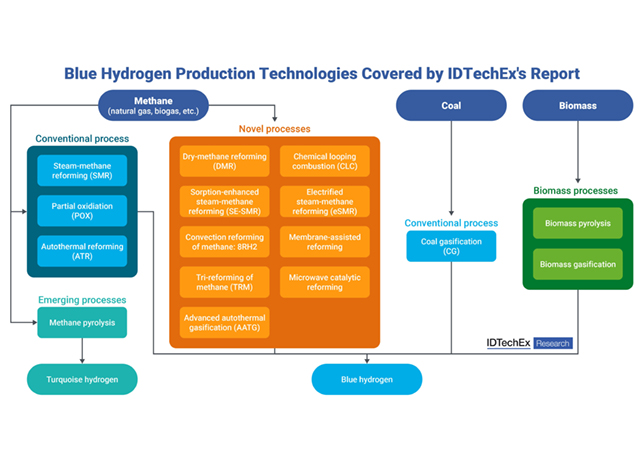

This level of nuclear baseload would liberate natural gas currently consumed for power generation for higher-value applications including petrochemical feedstock, liquefied natural gas export during price spikes, or green hydrogen production.

Current electricity generation remains 73.68 per cent natural gas-dependent.

Introducing 25-30 per cent nuclear baseload alongside existing renewable capacity targets would create genuine fuel diversity without grid stability complications.

Currently, Bahrain lacks dedicated nuclear regulatory infrastructure, operational experience pools, and specialised legal frameworks governing reactor licensing, fuel cycle management, and decommissioning liability.

The IAEA’s Country Programme Framework provides technical cooperation but cannot substitute for domestic capacity.

Singapore’s nuclear programme timeline, spanning pre-feasibility studies through 2025 capability-building towards potential 2030s deployment, illuminates the institutional development required.

Similarly, the UAE established its Federal Authority for Nuclear Regulation in 2009, three years before Barakah construction commenced, investing in regulator training, developing inspection protocols, and recruiting international expertise.

Bahrain would require comparable institutional development spanning 5-10 years minimum before any credible licensing process could commence.

Public acceptance constitutes another dimension, which Singapore addresses through systematic engagement campaigns explaining both benefits and risks.

Decommissioning planning represents frequently overlooked regulatory requirements.

The UAE’s Nawah Energy Company submitted decommissioning plans forecasting 13 years per reactor unit beginning five years after final shutdown, with costs potentially reaching several billion dollars.

Bahrain’s optimal strategy mirrors Singapore’s pragmatic gradualism: Commit to systematic capability development whilst monitoring SMR commercial deployments in Canada, the UK, and Poland that will validate or refute vendor cost and schedule claims.

At home, the UAE’s experience demonstrates that well-capitalised Gulf states can execute nuclear programmes when approached systematically with appropriate international technical support.

Bahrain could leverage existing Barakah operational data, UAE regulatory frameworks, and Korean vendor experience whilst avoiding first-of-a-kind risks by selecting proven small modular reactor designs approaching commercial deployment.

The critical insight distinguishes between having nuclear capability and exercising that option.

Singapore demonstrates that small states can build readiness infrastructure preserving strategic flexibility whilst avoiding catastrophic discovery in 2035 that nuclear would have been optimal but institutional capacity was never developed.

Similarly, Finland’s Olkiluoto 3, despite 14-year delays and triple-budget overruns, now provides 30 per cent of national electricity whilst reducing Russian import dependency by 60 per cent, validating nuclear’s long-term value proposition even when implementation proves difficult.

The question facing Bahrain is not whether to definitely deploy small modular reactors by 2035, but whether to position itself to make that decision from technical competence and strategic optionality rather than improvised desperation.

Singapore’s measured approach provides the answer: Invest in capability now, preserve options for deployment later, and ensure the kingdom controls its energy destiny rather than accepting whatever technologies remain available when crisis forces decision.

By Abdulaziz Khattak