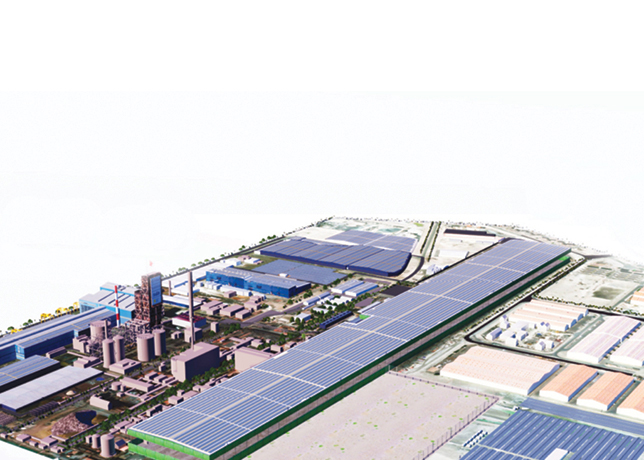

The world’s largest single-site rooftop solar power plant at Bahrain Steel will have a capacity of 50 MWp

The world’s largest single-site rooftop solar power plant at Bahrain Steel will have a capacity of 50 MWp

Despite leading commercial rooftop projects, Bahrain’s residential solar is negligible even as solar resources, falling PV costs and net-zero goals signal untapped potential

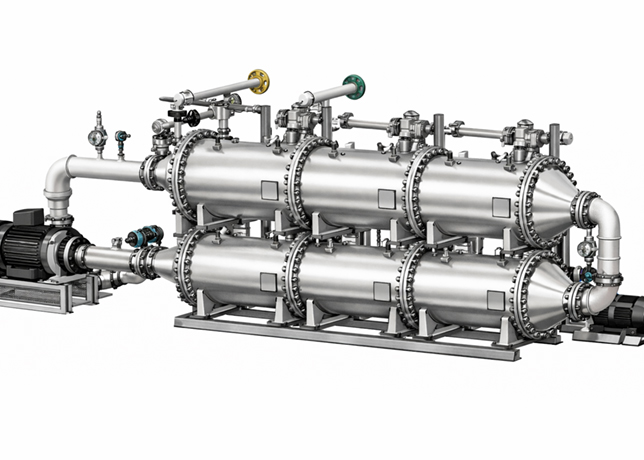

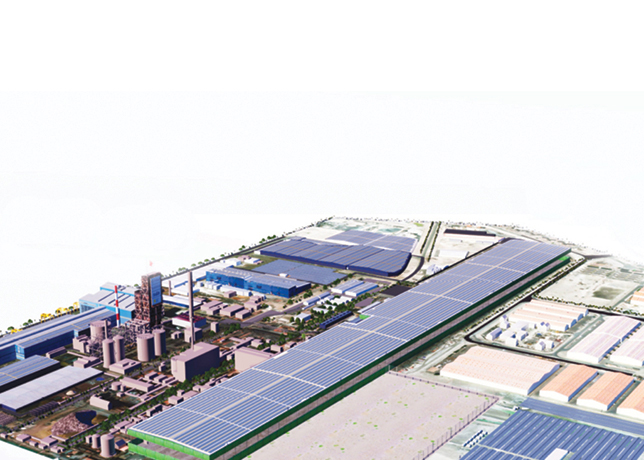

Bahrain's November 2025 announcement of the world’s largest single-site rooftop solar installation, a 50 MWp system spanning 262,000 sq m atop Bahrain Steel’s stockyard (a Foulath Holding company) shed, demonstrates the Kingdom’s technical and commercial viability of distributed photovoltaic (PV) generation.

Yet this industrial achievement, part of a broader 123 MWp programme developed by Foulath Holding and Yellow Door Energy, starkly contrasts with the Kingdom’s minimal residential rooftop adoption, exposing a fundamental disconnect between commercial-scale economics and household deployment barriers.

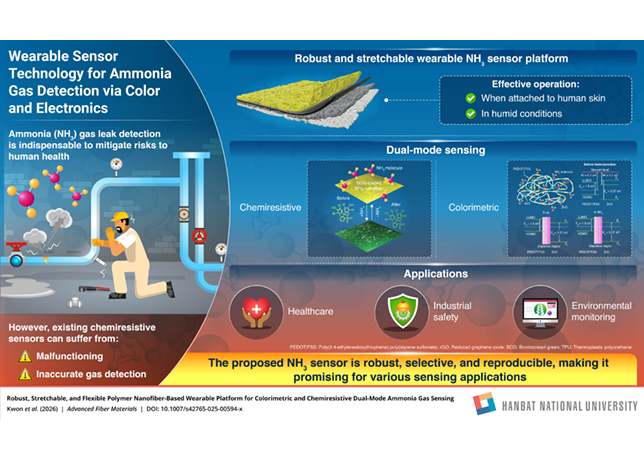

Bahrain’s solar resource base provides approximately 2,200 kWh per sq m annually at the optimum tilt angle of 26 degrees, and an average daily sunshine exceeding 10 hours, according to the Global Solar Atlas data cited in Oxford Academic’s Clean Energy journal.

Field studies of four government-supported domestic installations recorded specific yields ranging from 1,254 to 1,468 kWh/kW annually, substantially below theoretical projections.

As of late 2024, Bahrain’s cumulative solar capacity stood at 66 MW, representing 0.03 per cent of electricity generation in a 99.97 per cent natural gas-dependent grid.

The residential sector accounts for negligible capacity despite consuming over 50 per cent of the Kingdom’s total electricity production.

ECONOMIC HEADWINDS SUPPRESSING HOUSEHOLD DEPLOYMENT

Bahrain’s non-subsidised categories will see increases from 29 to 32 fils per kWh effective January 2026, though subsidised tiers for citizens remain unchanged.

These artificially suppressed tariffs fundamentally undermine rooftop solar economics.

Academic studies suggest purchase tariffs of 75 to 85 fils per kWh ($0.20 to 0.23 per kWh) with 30 per cent capital subsidies would enable viable residential deployment.

Alternative analyses proposed 100 fils per kWh ($0.27 per kWh) feed-in rates to achieve three-year payback periods for domestic installations.

Current net-metering frameworks, whilst operational since 2017 provide energy credits rather than monetary compensation, a mechanism deemed ineffective given Bahrain’s low consumption tariffs.

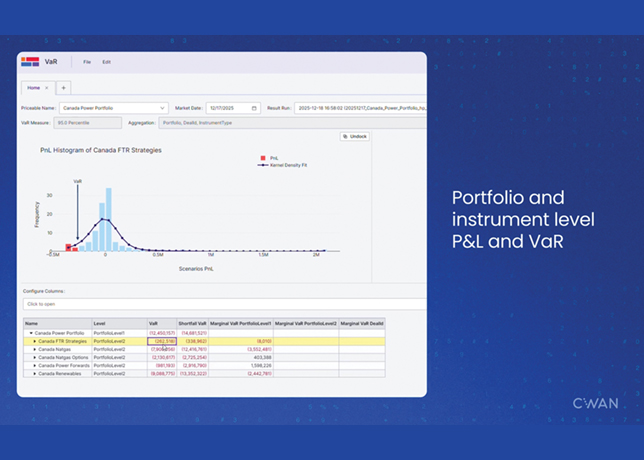

Projected levelised costs of electricity for solar photovoltaics range from $0.049 to 0.063 per kWh in 2025, declining to $0.036 to 0.055 per kWh by 2035.

These figures demonstrate technical cost-competitiveness against conventional generation yet fail to translate into household adoption drivers when retail tariffs remain below 5 US cents per kilowatt-hour.

Global residential system costs average $2.80 to 3.80 per watt in 2025, positioning a typical 7.8 kWp domestic installation between $21,840 and 29,640 before incentives.

Without robust financing mechanisms or substantial subsidies, these upfront expenditures exceed accessibility thresholds for most Bahraini households, particularly when extended payback periods eliminate investment rationale.

The government’s 2017 pilot programme installing 7.8 kWp systems on 10 residential buildings yielded valuable performance data but failed to catalyse broader market development.

Annual electricity generation from these pilot installations ranged from 9,995 to 11,448 kWh, with performance ratios between 65.6 and 75.1 per cent.

Feasibility analyses for Khalifa Town’s 1,724 villas concluded that 17 kW systems could meet 43 per cent of the settlement’s total electricity demand, generating 44,953 MWh annually, according to research published in ScienceDirect.

POLICY CHALLENGES

The Foulath-Yellow Door Energy programme operates under a 20-year power purchase agreement, with Yellow Door Energy financing, designing, constructing, and maintaining the installations.

The 123-MWp project spanning 707,000 sq m across 14 sites will generate approximately 200 million kWh in its first operational year, reducing carbon emissions by 90,000 metric tonnes.

Industrial off-takers benefit from avoided capacity investments whilst accessing clean energy at competitive rates through long-term contracts, arrangements unavailable to residential consumers.

The broader programme includes the 72 MW Sakhir multi-site development combining rooftop, ground-mounted, and car park installations.

Additional major projects include a 100-MW Al Dur utility-scale plant, a 150-MW Sakhir facility, and a 46.2 MW-University of Bahrain installation.

These utility and commercial-scale developments align with Bahrain’s National Renewable Energy Action Plan targets of 5 per cent renewable penetration by 2025 and 10 per cent by 2035, later revised to 20 per cent by 2035 following COP26 commitments.

The Kingdom’s Net-Zero by 2060 objective provides policy direction yet lacks the residential-focused interventions required to democratise rooftop solar access.

As of mid-2023, Bahrain’s installed solar capacity totalled approximately 57 MW, leaving substantial headroom for expansion.

The residential segment’s negligible contribution reflects not technical constraints but policy design prioritising large-scale deployment over distributed household generation.

Structural obstacles beyond economics compound residential deployment challenges.

Building stock varies considerably in roof suitability, with older constructions potentially requiring structural reinforcement to support panel loads.

Design aesthetics and social roof utilisation patterns—particularly for gathering spaces—constrain available surface area.

Architectural analyses of Khalifa Town housing revealed that structural and design limitations restricted approximately 65 per cent of total roof area from photovoltaic application.

ENVIRONMENT-DRIVEN OPERATIONAL DEMANDS

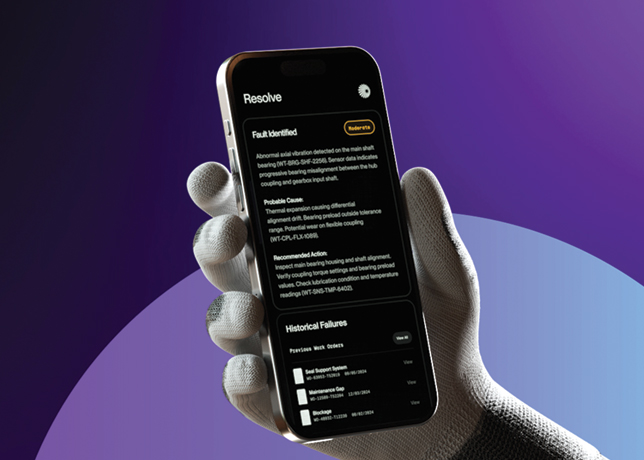

Bahrain’s desert climate generates frequent dust accumulation on panel surfaces, reducing generation efficiency whilst high ambient temperatures lower PV performance relative to standard test conditions.

Without clear government guidance or standardised quality benchmarks, homeowners face information asymmetries potentially deterring adoption.

The contrast with successful regional models highlights Bahrain’s policy gaps.

Jordan’s aggressive feed-in tariff structures and net-metering implementation have driven significant residential deployment.

The UAE has advanced distributed generation through Dubai’s Shams initiative and Abu Dhabi’s regulatory frameworks supporting prosumer models.

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 renewable targets include specific residential solar provisions with enabling regulatory architectures.

Bahrain possesses comparable or superior solar resources yet lacks the incentive structures catalysing household participation.

By Abdulaziz Khattak