Sipchem ... using sukuk to fund infrastructure projects

Sipchem ... using sukuk to fund infrastructure projects

PROJECT Islamic bonds are expected to pick up steam in Saudi Arabia with the launch of the first project sukuk this month as issuers seek to diversify sources of funding following global financial woes that may dry up lending from international banks.

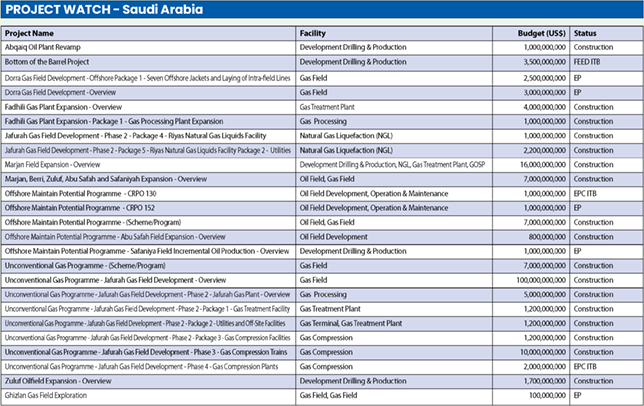

Saudi Arabia, with projects under way worth $623 billion according to the economic weekly Meed, is the largest Gulf markets and is expected to require billions of dollars in financing. Financing has traditionally come from government funds and syndicated loans from local and international banks.

But the launch of the kingdom’s first project sukuk instrument earlier this month – a $1 billion Islamic bond to be issued by Saudi Aramco Total Refining and Petrochemical Co (Satorp) – is expected to provide a financing alternative and open the doors for more issuance to come.

“The sukuk issuance does potentially change the game quite significantly,” says Jarmo Kotilaine, chief economist at National Commercial Bank in Riyadh.

“Most issuers aren’t innovators, they are replicators. But there are now advisors out there that are in the position to offer similar solutions. It will generate interest.”

That interest comes at a good time as international banks struggle with mounting global economic fears as well as their own balance-sheet woes, making lending less attractive.

“Although it is very likely that a core group of banks will continue to lend to projects in the region, aggregate debt capacity will be eroded and the price of liquidity will likely become more expensive,” says Andrew Davison, senior vice president and team leader of EMEA project financing at Moodys.

That creates opportunity for the sukuk market to become an increasingly important potential source of funds, he adds.

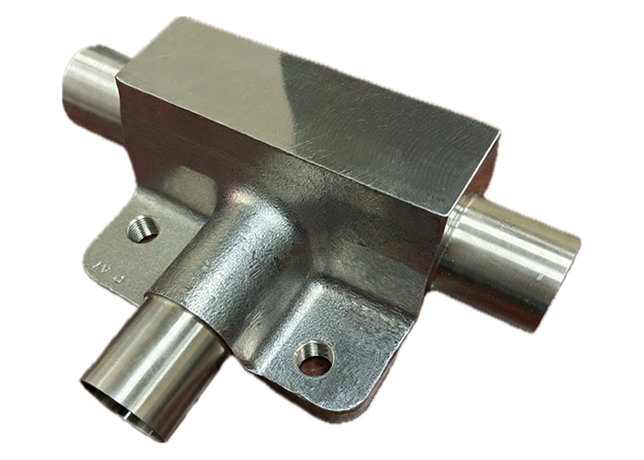

But issuing project sukuk has been a piecemeal proposition so far. Issuers, such as Saudi International Petrochemical Co (Sipchem), have used sukuk proceeds to partially finance infrastructure projects.

While the offering was oversubscribed, indicating demand, a pure-play project bond had yet to be offered.

Satorp’s instrument – a musharaka agreement in which holders become the owners of the project or the assets of the activity – will be used to finance its planned 400,000 barrels per day crude oil refinery in Jubail.

Initial price guidance for the sukuk is seen at 6-month Saudi interbank offered rate (Saibor) plus 95-105 basis points.

Final pricing could provide an idea of the demand for such a project, fuelling further offerings, says Nabil Issa, partner at King & Spalding in Dubai.

“It’s about letting someone else do the homework first, overcome the regulatory hurdles and invest the time and money to prove it can be successful,” he says.

“I think you’ll see a lot more projects being financed by sukuk and becoming more popular after this.”

But structuring a sukuk does come with challenges that have prompted potential issuers to seek other forms of financing such as conventional loans or a commodity murabaha, a cost-plus-profit transaction.

Sukuk can be time-consuming and more costly, involving the creation of a special purpose vehicle which uses the sukuk proceeds to pay a contractor to build a future project. And there’s no standardised documentation for a sukuk structure.

But there is more willingness now to gain familiarity with sukuk as an alternative.