Karan ... promising more gas supplies

Karan ... promising more gas supplies

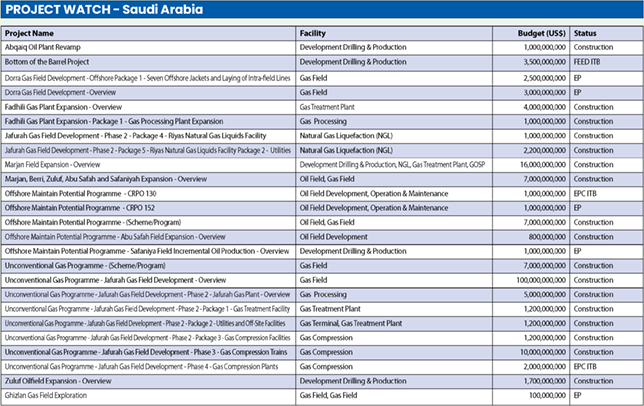

SAUDI Arabia is focusing on developing its conventional gas reserves and expanding its downstream refining and chemicals industries rather than invest in expanding oil production.

Saudi Arabia has plenty of gas and the state has decided to focus on production of that for the time being. But much of it is sour, which makes it problematic. “Given the increased availability and distribution of oil reserves, I think there was pressure on the kingdom and on Saudi Arabia to raise production beyond the needs of Saudi Arabia. That pressure I would see is substantially reduced,” Saudi Aramco CEO Khalid Al Falih says.

“Our focus is to invest heavily in gas, in downstream, in refining and, something that is new to Aramco, in chemicals,” Al Falih says, adding that this would provide the state-owned company a global footprint.

The scale of projects that Saudi Aramco is undertaking in China, South Korea as well as mega projects in the downstream at home “are equal to and sometimes eclipse what we are doing in the upstream,” he adds.

Saudi Arabia has total crude oil production capacity of 12.5 mbpd and has no further investments planned to expand that further although its energy minister Ali Naimi has said previously that the Opec kingpin could raise capacity to 15 mbpd if demand required it.

Saudi Aramco is also planning to develop its shale gas resources in the future and plans to drill a number of wells this year to test the geology of the wells and conduct preliminary economic models, he says.

“We will continue that in 2012 and we have pilots in various areas where economics are favorable and directed toward regional power generation and industry,” he added. While the resource base is “large,” Saudi Aramco will continue to focus on developing its conventional gas reserves with two major gas plants due to come into production soon, Al Falih says.

“So our short to medium term [strategy] is to rely on conventional gas reserves and bringing them to the market,” he says. As for shale, “it’s still early days to give a time frame but we know the resource base is there.” Nuclear energy was also being considered but that would take time to develop. “It’s nothing that’s going to change the energy mix of the kingdom soon,” Al Falih says.

Saudi Aramco has started developing its first non-associated gas field, the Karan field, as part of an effort to supply its ever expanding chemicals and petrochemicals sectors while also meeting high domestic demand for power generation and desalination plants.

Khalil Al Shafei, who is the interim president of the King Abdullah Petroleum and Research Centre, says that, if the current demand pattern continued, Saudi Arabia would be using 8 million barrels of oil equivalent per day (mboepd) domestically by 2035.

“By 2035, the kingdom’s consumption of primary energy – including oil, gas, and natural gas liquids – could reach roughly eight mboepd, assuming no change in the current status. Huge investments in the domestic energy value chain are needed to meet this demand, from crude and gas production to electricity generation and distribution,” Shafei says.

But Al Falih, without referring specifically to Shafei’s figure, says the kingdom had several “holistic initiatives and programmes” to manage consumption and “take our energy intensity to a competitive level.”

“I think there are a number of programs being undertaken to manage the demand side and which I think will lead to a flattening or reduce the slope of demand... in the future, we are counting on gas to take more and more of the load on local energy applications, power, water, desalination, industrial application.

“The kingdom has established the view... that will target diversifying the energy mix away from oil and gas. We are bringing more conventional and unconventional gas... diversification with solar, eventually wind where it can be competitive, and nuclear... in managing the demand side, I don’t see this as a threat to the kingdom being the global supplier of petroleum that it has been,” Al Falih says.

Saudi Aramco is also working – with Anglo-Dutch Shell – on the high-sulphur Kidan gas discovery in the Saudi Rub Al Khali desert and has agreed to invest in the appraisal phase of the project though it has not yet taken a final decision on developing it, Al Falih says.

Aramco sells gas to local industry and utilities at a relatively low price of $0.75/mmBtu, rather than for export. Al Falih was asked whether this price would now be revised given the higher cost of developing sour gas reserves. He says the decision was up to the government but that the plans to develop the kingdom’s natural gas reserves, the fourth largest in the world, would proceed regardless.

“We will wait for the government to make that decision but we look at the economics from a kingdom perspective and if the gas is displacing liquids that are currently being burned, then from a kingdom perspective it makes sense to convert now in making that gas ready to be developed and I am confident that the government will make the right decision,” Al Falih says.

In his presentation to the hundreds of delegates attending a conference in Riyadh, Al Falih says the world of energy, which he says is in a constant state of flux, had been transformed by the increasing focus on non-conventional oil and gas resources. There is an abundance of oil and gas and new technological advances were unlocking additional resources, he adds.

“A few years ago, much of the global energy debate was based on the premise of acute resource scarcity and its economic and political ramifications. Policy and investment choices have therefore largely been framed against a backdrop of constrained oil and gas resources and a need to transition with deliberate speed to one or more alternatives,” Al Falih says.

“Today, talk of oil and gas scarcity has disappeared from both the energy press and the general media, to be replaced by news of increasingly plentiful supplies,” Al Falih says.

Whereas five years ago, there was talk of the need to build new LNG terminals in the US and of the overdependence of European consumers on Russian gas, “now by contrast, the challenge is finding an ‘outlet’ for the new production of shale gas, and downward pressure on natural gas prices,” he adds.