Mubarak ... digital transformation focus

Mubarak ... digital transformation focus

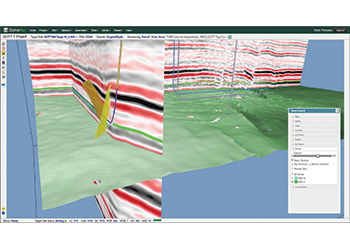

All industries have recognised that digital technologies make it possible to provide more efficient, accurate, and timely information to decision makers. They have implemented digital and intelligent technologies and have already realised numerous benefits.

However, leaders realise that neither can the full value of any transformation be achieved by implementing strategies of the past, nor will it be realised by implementing fragmented optimisation efforts. The distinguishing factor is a clear demonstration of the difference between those who participate in the future and those who make it, says Saeed Mubarak, a thought-provoking author.

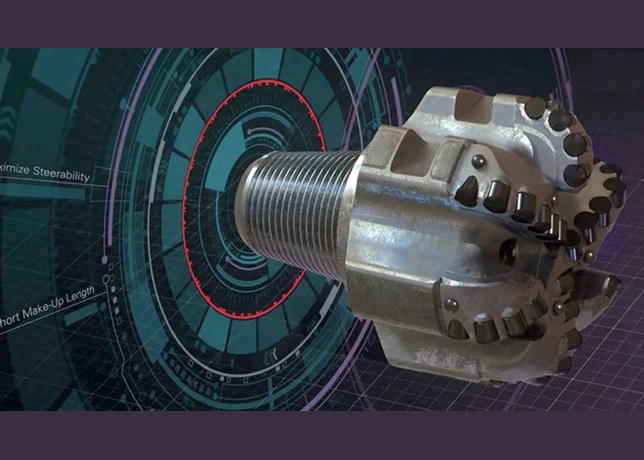

Although, this work focuses on Digital Oil Fields (DOF), yet the same philosophy can be applicable to any digital transformational endeavour in any industry. Some of the content is based on actual survey results, on field observations, and on rational speculation about future trends and advances in DOF technologies and their implementation.

The infusion of digital technologies into hydrocarbon upstream industries has significantly impacted the exploration and production (E&P) business environment. Pioneers are still exploring venues in this regard.

Most DOF projects have shown good potential but have been degraded performance due to both technical and business lack of readiness. In terms of implementation, many approaches have been developed around existing vendor products rather than around work processes they wish to improve.

The marketplace, in general, has undergone five phases of learning about DOF: technology; value realisation; people, process and technologies; value realisation; and business value architecture.

Five essential progressive steps towards the DOF’s maximum value

LESSONS ON DOF INITIATIVES

As a part of our pursuit of the DOF, surveys were conducted to evaluate the state of our transition to digitally enhanced work processes, and to find out what professionals might need for their future development. The survey results were summarised as follows:

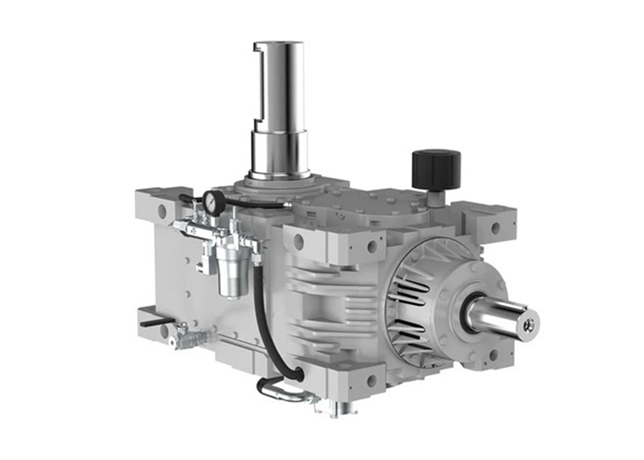

• Most of the available DOF expertise is on technologies (hardware), with fewer experts on strategies, integration, optimisation and implementation.

• Most contributing constraint preventing operators to adapt to DOF are lack of experience and tolerance to change (that is, people).

• While most of the participants see DOF endeavors add great value and create more opportunities, others see DOF introducing more complexities and additional expenditure.

• The greatest potential value of DOF implementation is expected to come out of optimisation, informed and predictive operations. Less value can be seen from knowledge management or technologies.

• Better integration and optimisation is seen as the greatest value earned from implementation of DOF with the least value of it on improving HSE.

Based on this summary, some realistic conclusions and expectations include:

• The industry needs more experts in optimisation, predictive and informed operations.

• DOF added value and created opportunities.

• The understanding of DOF technologies and expertise is still maturing.

• A clearer path to achieve the maximum value of DOF is a result of continuous improvement in combined endeavors that capitalise on the orchestration of technologies, knowledge management, business intelligence, analysis and optimisation.

Asset managers have to decide how to incorporate DOF to business, realising that it comes as a supplement and will not change a strategy nor will it change the fundamentals. Among the goals are: reducing opex and capex, maximising production, sustaining production, maximising recovery, minimising operation time, and improving HSE.

The aim of DOF should be to eliminate work duplication not to add to work. Hence, DOF should make things easier, as opposed to making things more complicated.

The answers to one question in the survey gave us pause: Why is the industry still not getting the maximum value of DOF? The answers pointed to a "lack of experience and tolerance to change" as the most important reason.

After examining the survey results, studying journal literature, and using common sense, we high-graded three critical DOF improvement imperatives that could be taken to help DOF professionals with their work: Aligning organisational structure for DOF; Clarifying business needs and expectations; and Strengthening people competencies.

• Aligning organisational structure for DOF: Organisational elements are optimised over time around core work processes, and an organisation needs to make sure that its structure is built to perform the strategy its management has set out.

DOF must be supported by business value architecture (BVA), which can be described as a combination of three different structures that must be aligned and integrated to maximise their business potential value. The strategic business architecture includes the company’s DOF vision and strategic goals, measures, and incentives; the work process architecture includes the matrix of technical and business work processes needed to achieve the organisation’s strategic goals driven by DOF; and the technical process architecture includes the processes inside the IT or R&D organisation to manage the digital resources required to enable work processes and enterprise optimisation.

What comes next to this imperative is a progressive and continuing development of a clear set of roles and responsibilities for the business with means to communicate them to relevant parties.

• Clarifying business needs and expectations: Ownership in the era of the DOF is required at all levels of the company. Having various DOF project team members involved early in the development stages of DOF allows ownership over their own DOF segment performance. This, in turn, helps them develop a sense of responsibility and self-motivation. If these roles and responsibilities are not well defined and performed effectively, DOF success will be doubtful.

The four levels include the executive management, which sets the DOF strategy and balances resources; senior management, which builds DOF and organisational capabilities; middle management, which validates new DOF capabilities while running-the-business; and supervisors, who lead employees to be ready, willing and able for DOF performance.

• Strengthen the competencies of industry professionals: The fundamentals of the petroleum industry have not changed much; however, the evolution of the various technologies has surfaced out a new set of expertise, knowledge and competencies. Any DOF training or development program has to be fine-tuned to avoid dilution of current skills base.

In the new business environment, petroleum engineers need to know more about DOF technologies and IT and vice versa. Add to this mix business principles. This business addition has to do with principles associated with work process design and engineering along with program and project management.

While the three competencies are obviously all needed to work the kind of process improvement described earlier, they do not have to reside in a single person. A three-person team might be able to pool their resources and have what it takes for the job. The key to achieve the maximum value is ownership and collaboration. Among the essentials that DOF teams must know, include:

• Work process architecture: A work process architect would be an expert on the work process architecture, knowing interdependencies, recognising strong and weak points, and being able to identify the ‘leverage points in the architecture’ that have the highest potential for improvement with better design and/or information technology.

• Work process engineering: Work process engineering includes expertise in identifying, improving, and streamlining workflow as well as identifying the needed interfaces with digital technology, to produce additional business value.

• Programme management: Programme and project management provide the needed techniques, tools, and discipline to direct a programme of work that includes process redesign, selection of technology, and both the ‘readying of the technology for the organisation’ and the ‘readying of the organisation for the technology.

One of the main functions of the DOF team is to create business environments driven by and aligned with the advancements and integration of DOF.

An ideal DOF team consists of both strategy and tasks disciplines who have sufficient expertise and horsepower to properly embed initiatives across the design, install and operate phases of DOF. While the strategy team applies a top-down approach, the tasks team adopts a bottom-up approach.

It is both ideal and obvious for DOF to be embedded in the company strategies, structure and roles and responsibilities, etc. What is not obvious (to some) is the importance of still having a DOF corporate team with specific focus and responsibilities to ensure high quality and consistence practice of DOF within an organisation. The answer to that can be:

• Organisations are hard to change: Mature organisations are designed as ‘stability structures’ that max efficiency and limit variation (that is, change). Organisational change must be planned, authorised and led for business value.

• Actual DOF company structure is most likely to be the original company structure overlaid with DOF initiatives. The inertia tends towards original company structure unless is worked hard by dedicated program that is maintained.

• Continue to pursue DOF, but use an orderly and disciplined process. There is no need to ‘reinvent the wheel’ for implementation.

• Continue to build capabilities: People, management and organisational support capabilities.

• Concentrate on working top down, bottom up, and sideways.

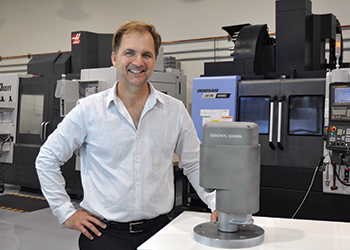

Saeed Mubarak is a thought-provoking author, who has published tens of articles and several programmes to promote innovation, and challenge conventional wisdom within and beyond the petroleum industry. He is a recognised technical and inspirational author and speaker demonstrating the significance of digital transformation and intelligent fields.

Mubarak is company Intelligent Fields focus area champion at Saudi Aramco, based in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. He serves as Chairman of SPE international Digital Energy Technical Section (DETS); and an advisory committee member in the SPE DSEA and Texas A&M SPE student chapter. His contributions to the area of intelligent energy and innovation have been recognised by renowned technical, governmental and social authorities.

.jpg)