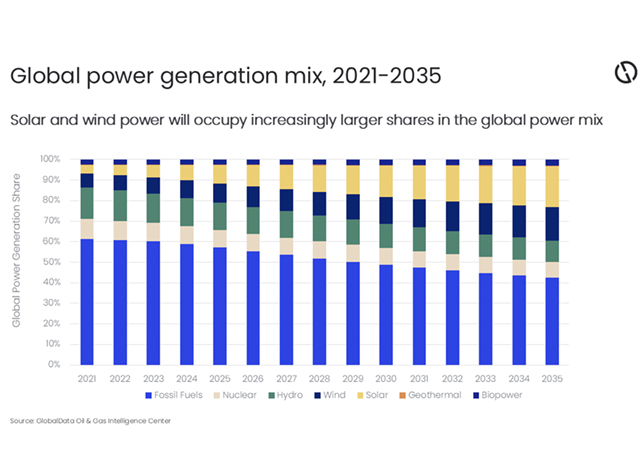

Aramco, for its part, argues oil and gas will remain at the heart of the energy mix for decades, saying renewables and nuclear cannot meet rising global demand, and that its crude production has lower greenhouse gas emissions than its rivals

The state energy giant’s vast oil reserves – it can sustain current production levels for the next 50 years – make it more exposed than any other company to a rising tide of environmental activism and shift away from fossil fuels.

In the three years since Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman first proposed a stock market listing, climate change and new green technologies are putting some investors, particularly in Europe and the United States, off the oil and gas sector.

Sustainable investments account for more than a quarter of all assets under management globally, by some estimates.

Aramco, for its part, argues oil and gas will remain at the heart of the energy mix for decades, saying renewables and nuclear cannot meet rising global demand, and that its crude production has lower greenhouse gas emissions than its rivals.

But with the company talking again to banks about an initial public offering (IPO), some investors and lawyers say the window to execute a sale at a juicy price is shrinking and Aramco will need to explain to prospective shareholders how it plans to profit in a lower-carbon world.

“Saudi Aramco is a really interesting test as to whether the market is getting serious about pricing in energy transition risk,” said Natasha Landell-Mills, in charge of integrating environment, social and governance (ESG) considerations into investing at London-based asset manager Sarasin & Partners.

“The longer that (the IPO) gets delayed, the less willing the market will be to price it favorably because gradually investors are going to need to ask questions about how valuable those reserves are in a world that is trying to get down to net zero emissions by 2050.”

Reuters reported on Aug. 8 that Prince Mohammed was insisting on a $2 trillion valuation even though some bankers and company insiders say the kingdom should trim its target to around $1.5 trillion.

A valuation gap could hinder any share sale. The IPO was previously slated for 2017 or 2018 and, when that deadline slipped, to 2020-2021.

Aramco told Reuters it was ready for a listing and the timing would be decided by the government.

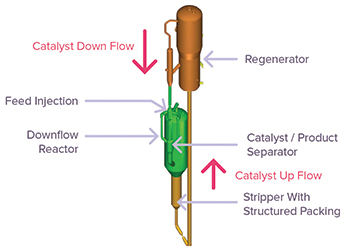

The company also said it was investing in research to make cars more efficient, and working on new technologies to use hydrogen in cars, convert more crude to chemicals and capture CO2 which can be injected in its reservoirs to improve extraction of oil.

Some would argue this is not enough.

A growing number of investors across the world are factoring ESG risk into their decision-making, although the degree to which that would stop them investing in Aramco varies wildly.

Some would exclude the company on principle because of its carbon output, while others would be prepared to buy if the price was cheap enough to outweigh the perceived ESG risk - especially given oil companies often pay healthy dividends.

At a $1.5 trillion valuation, Aramco would be the world’s largest public company. If it were included in major equity indices it would automatically be bought by passive investment funds that track them, regardless of their ESG credentials.

And as the world’s most profitable company, Aramco shares would be snapped up by many active investors.

Talks about a share sale were revived this year after Aramco attracted huge investor demand for its first international bond issue. In its bond prospectus, it said climate change could potentially have a “material adverse effect” on its business.

When it comes to an IPO, equity investors require more information about potential risks and how companies plan to deal with them, as they are more exposed than bondholders if a business runs into trouble.

“Companies need to lead with the answers in the prospectus, rather than have two or three paragraphs describing potential risks from environmental issues,” said Nick O’Donnell, partner in the corporate department at law firm Baker McKenzie.

“An oil and gas company needs to be thinking about how to explain the story over the next 20 years and bring it out into a separate section rather than hiding it away in the prospectus, it needs to use it as a selling tool. And also, once the IPO is done, every annual report should have a standalone ESG section.”

Unlike other major oil companies, Aramco doesn’t have a separate report laying out how it addresses ESG issues such as labor practices and resource scarcity, while it does not publish the carbon emissions from products it sells. Until this year’s bond issue, it also kept its finances under wraps.

The company does however have an Environmental Protection Department, sponsors sustainability initiatives and is a founding member of the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, which is led by 13 top energy companies and aims to cut emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

On August 12 Aramco published information on the intensity of its hydrocarbon mix for the first time. It disclosed the amount of greenhouse gases from each barrel it produces.

Aramco’s senior vice president of finance Khalid Al Dabbagh said during an earnings call this month that its carbon emissions from “upstream” exploration and production were the lowest among its peers.

A study published by Science magazine last year found carbon emissions from Saudi Arabia’s crude production were the world’s second lowest after Denmark, as a result of having a small number of highly productive oilfields.

Aramco says that, with the global economy forecast to double in size by 2050, oil and gas will remain essential.

“Saudi Aramco is determined to not only meet the world’s growing demand for ample, reliable and affordable energy but to meet the world’s growing demand for much cleaner fuel,” it told Reuters.

“Alternatives are still facing significant technological, economic and infrastructure hurdles, and the history of past energy transitions shows that these developments take time.”

The company has also moved to diversify into gas and chemicals and is using renewable energy in its facilities.

But Aramco still, ultimately, represents a bet on the price of oil.

It generated net income of $111 billion in 2018, over a third more than the combined total of the five “super-majors” ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Chevron and Total.

In 2016, when the oil price hit 13-year lows, Aramco’s net income was only $13 billion, according to its bond prospectus where it unveiled its finances for the first time, based on current exchange rates. Its earnings fell 12 per cent in the first half of 2019, mainly on lower oil prices.

Concerns about future demand for fossil fuels have weighed on the sector. Since 2016, when Prince Mohammed first flagged an IPO, the 12-months forward price to earnings ratio of five of the world’s top listed oil companies has fallen to 12 from 21 on average, according to Reuters calculations, lagging the FTSE 100 and the STOXX Europe 600 Oil & Gas index averages.

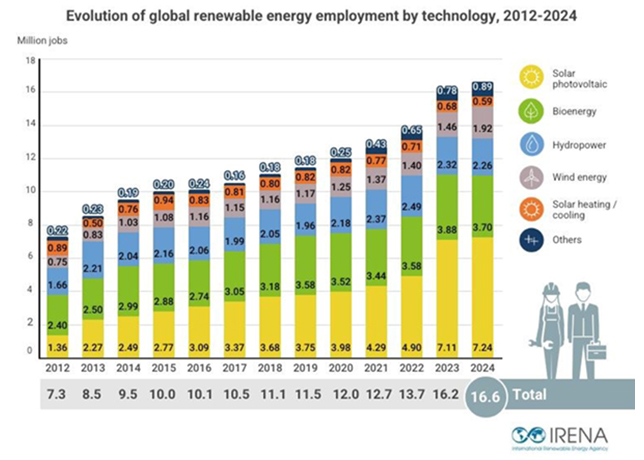

By comparison, UK-listed funds investing in renewable energy infrastructure such as wind farms are trading at one of the biggest average premiums to net asset value.

Using a broad measure, there was global sustainable investment of $30.1 trillion across the world’s five major markets at the end of 2018, according to the Global Sustainable Investment Review, more than a quarter of all assets under management globally. That compares with $22.8 trillion in 2016.

“Given the influx of capital into the ESG space, Aramco’s IPO would have been better off going public 5-10 years ago,” said Joseph di Virgilio, global equities portfolio manager at New York-based Romulus Asset Management, which has $900 million in assets under management.

“An IPO today would still be the largest of its kind, but many asset managers focusing solely on ESG may not participate.”

The world’s top listed oil and gas companies have come under heavy pressure from investors and climate groups in recent years to outline strategies to reduce their carbon footprint.

Shell, BP and others have agreed, together with shareholders, on carbon reduction targets for some of operations and to increase spending on renewable energies. US major ExxonMobil, the world’s top publicly traded oil and gas company, has resisted adopting targets.

Britain’s biggest asset manager LGIM removed Exxon from its 5 billion pounds ($6.3 billion) Future World funds for what it said was a failure to confront threats posed by climate change. LGIM did not respond to a request for comment on whether it would buy shares in Aramco’s potential IPO.

Sarasin & Partners said in July it had sold nearly 20 per cent of its holdings in Shell, saying its spending plans were out of sync with international targets to battle climate change. The rest of the stake is under review.

The asset manager, which has nearly 14 billion pounds in assets under management, didn’t participate in Aramco’s bond offering and Landell-Mills said they would be unlikely to invest in any IPO.